From the desk of Amanda Lang, who attended and spoke at the Forest Landowner’s Association National Conference last week in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida.

“Forest certification” generated lots of questions from those attending the 2012 Forest Landowner’s Association national meeting. Who is certified? Which program do they use? Why? Does it make sense for forest landowners to participate in these programs? What do they accomplish when research indicates state-based forest management programs achieve similar improvements in forest and water quality?

First, let’s define our terms. Forest certification includes third-party programs that guarantee sustainable forest management based on a standard set of criteria. An established forest certification program in North America is the Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI). In 2005, the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification endorsed SFI, giving it international recognition. The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), based in Oaxaca, Mexico, is a major international certifier. The American Tree Farm System (ATFS) supports a program for nonindustrial family forest owners in the United States.

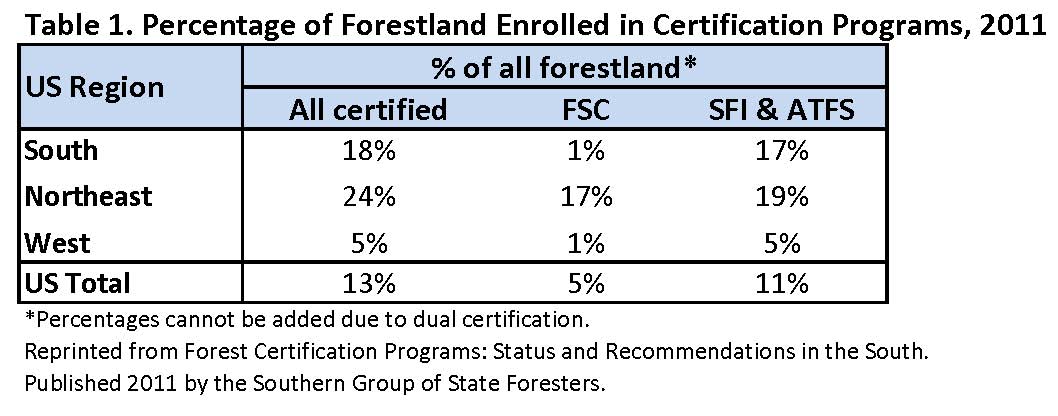

In November 2011, the Southern Group of State Foresters published a report about the status of forest certification in the U.S. (available here). By region, the Northeast has the highest percentage of forestland enrolled in certification programs, followed by the South (Table 1). Most acres enrolled in FSC certification are located in the Northeast while the South favors SFI and ATFS programs.

Currently, most wood buyers do not pay premiums for certified wood. The profile of landowners enrolled in SFI or FSC programs are industrial owners that participate in certification as an industry standard and to satisfy investor requirements for sustainable management and public relations. Typically, small or nonindustrial private landowners either participate in ATFS or not at all.

If markets develop for certified wood and buyers offer premiums for certified wood, then landowner participation in these programs will increase. Currently, few incentives exist for the nonindustrial private landowner to certify. In fact, private landowners remain skeptical of incurring extra costs for programs that seem to mirror their existing sustainably-oriented forest management plans. This feeling has been reinforced by research that shows state-mandated management practice guidelines provide effective means to protect water quality*. For example, when best management practices are followed, water quality on stands in the South recovers in 2-5 years following a timber harvest. Research in the Pacific Northwest also confirms that buffer zones along stream banks allow water systems to recover following timber harvest.

*Lang, A.H. and B.C. Mendell. 2012. Sustainable wood procurement: What the literature tells us. Journal of Forestry. 110(3): 157-163.

Leave a Reply