While I hesitate to use the phrase “can’t see the forest for the trees” when analyzing the timber industry, it does feel relevant when tracking trends and processing the floods of data coming at us in the modern world. Peter Senge, an MIT management professor and author said, “Reality is made up of circles, but we see straight lines.” A similar concept that suggests failing to consider the bigger picture misses the real story. Initially, this thought troubled me when evaluating the latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The data indicates year-over-year logging employment fell in every region of the country for the first time since the recession ended. Does this threaten a growing forest industry? Not necessarily.

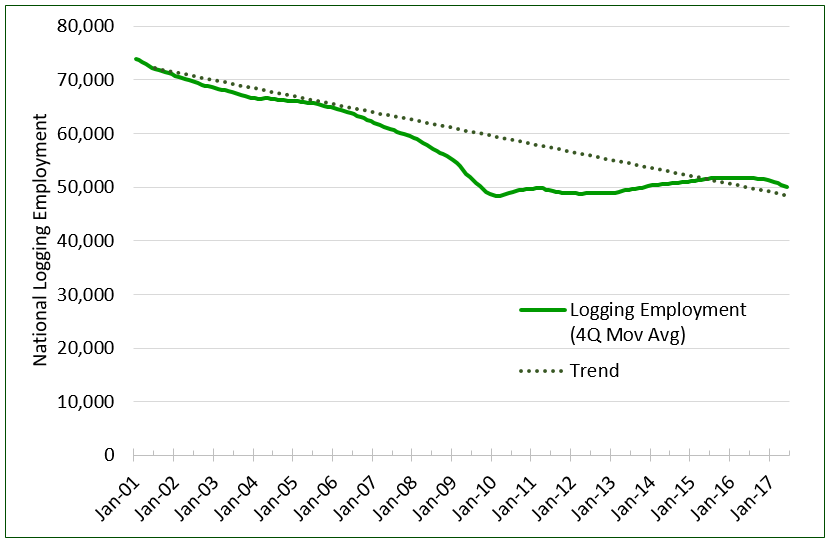

Heading into the recession, national logging employment had been dropping for years, despite tremendous production growth feeding a surging housing market. Logging productivity outpaced demand growth. From 2001 to 2006, the logging industry lost 120 workers per month, on average.

During the recession, we lost about 25% of the logging workforce. In the years since the recession, we’ve seen moderate growth in employment paired with substantial increases in wood demand, particularly for sawtimber. Why, then, is logging employment dipping?

A simple linear trend offers a clue (Figure 1). If we had continued to lose loggers at the pace witnessed prior to the recession, we would be at roughly our current level of employment. Productivity and efficiency gains in the industry continued through the recession. The job losses accelerated the pace at which the industry improved its efficiency. The businesses that survived were financially challenged but operationally well-positioned to thrive as markets recovered. Not to mention that a larger proportion of that output is shifting to the South, a region with the highest production per logging employee in the country.

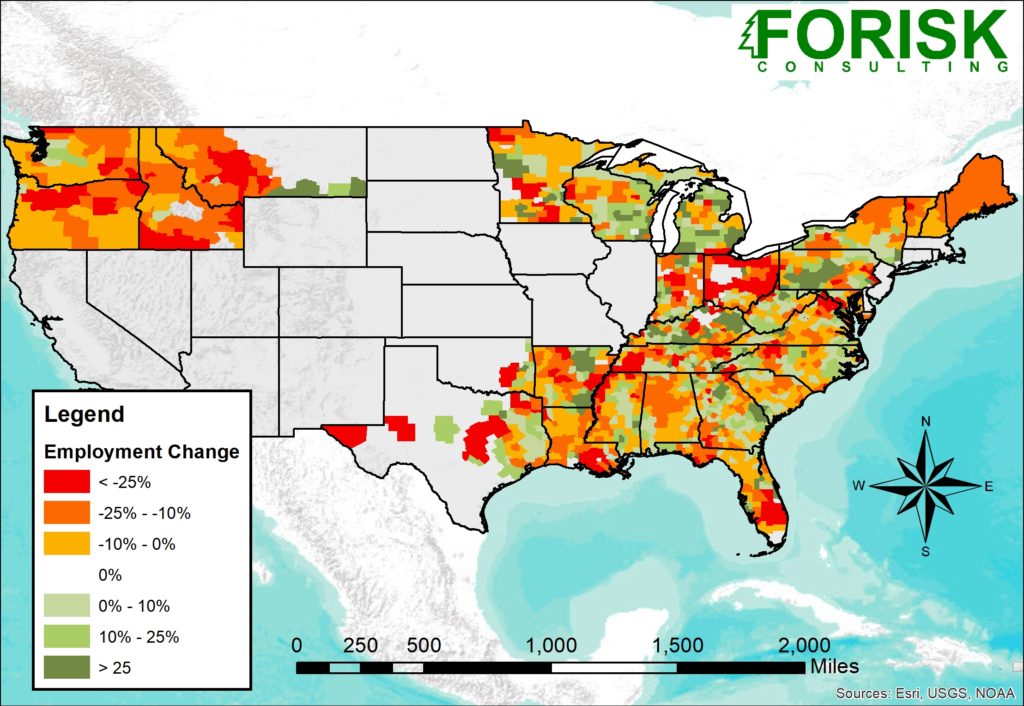

The idea that employment will continue to decline linearly is untenable. A downward-trending straight line goes to zero. And wood demand continues to grow. At some point we approach the limits of productivity improvements. It is unlikely we’ll develop a Paul Bunyan capable of providing all of the nation’s wood needs with a single axe. In fact, employment continues to grow locally in markets with strong demand; employment is not declining in every wood basin (Figure 2). As we often note, timber markets are uniquely local. Logging employment is another piece of the story when evaluating local markets.

Hello Shawn,

This article mentions/implies that the net loss of logging workers is being offset primarily with productivity gains and a mix of higher percentage of logging in the south which is higher production relative to the other regions. Do you have any data or articles that explains/shows the gains in productivity on a per worker/by region on a timeline? Anything you have that would show how modern equipment is filling the gap?

Roger: Thanks for the questions. We posted some information on trends in western productivity on the blog a couple years ago which you can find here. In terms of the same trends in the South, the best data on that comes from long-term studies which have tracked productivity over time. The best source I know of is the University of Georgia’s logging contractor survey, which now has 30 years of data showing a continuous increase in output per man-hour. Those get reported every five years in places like the Forest Resources Association Technical Releases (the last was in 2013, but a new one should be forthcoming soon).