Time has a funny way of passing. Sometimes it seems to zoom by (college years) and others it just crawls (high school lectures on voodoo economics). For an industry grounded in decades-long timeframes, forestry can sometimes feel quite dynamic. This year is a great example, as whiplash affects anyone following lumber or pulp prices over the past 12 months. The logging sector is not immune to the winds of change, either. Twenty years ago, my colleagues completed a detailed survey of the costs of unused logging capacity in the United States. Today, the logging industry is nearly 40% smaller and unused capacity is no longer a leading issue of concern. Instead, much of the industry is clamoring for truck drivers to move wood to mills and fearing further contraction of in-woods labor.

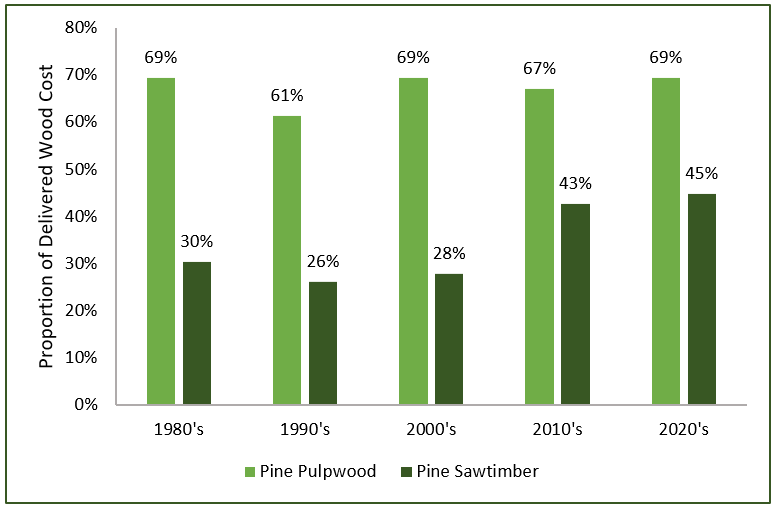

The cost of harvesting and transporting timber is a significant portion of total delivered cost, particularly for pulpwood-sized material. Even for sawtimber, stumpage[1] is no longer as large a portion of delivered cost as in the recent past (Figure 1). Harvesting and delivery costs average around 70% of the cost of pulpwood in the southern U.S. For sawtimber-sized products, logging and hauling costs increased from 30% of the delivered cost of wood in the 1980’s to 45% over the first two years of the 2020’s.

Given current concerns over logging and hauling capacity, it is reasonable to question whether costs may increase in the near term. History provides some clues but no clear answers. Over the last 40 years, the cost of logging and hauling[2] increased at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 2.0% per year. In comparison, inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index, increased at a CAGR of 2.9%. Looking at a sliding 10-year window of logging cost growth (e.g. a CAGR calculated in 2000 would represent the average annual cost increase from 1990 to 2000), from the mid-1990’s to around 2014, logging cost CAGRs consistently exceeded the long-term average (Figure 2). Since 2014, the 10-year CAGR fell below 2% and remained there. Looking specifically at the spread between stumpage and delivered costs from 2014 through 2021, the CAGR is only 0.5%.

This is a technical way of saying that logging and hauling costs were historically stable for the past seven years. Until 2021, inflation was quite low for much of this period as well. Given supply concerns across North America, it is fair to question if this slow cost growth may end soon.

Interested in learning a process for tracking and analyzing the price, demand, supply and competitive dynamics of local timber markets and wood baskets? Register here for Forisk’s 2021 “Timber Market Analysis” class, offered virtually via Live Zoom webinar on December 8th and 9th. (The content of Day 2 builds on Day 1). We guarantee no Ben Stein impersonations.

[1] The cost of wood paid to landowners

[2] Here we use the difference between delivered costs and stumpage costs to proxy logging and hauling costs. Procurement and other administrative costs are a component of the spread between the two, but logging and hauling will comprise the largest portion of the difference.

Just curious, is the logging costs the actual out of pocket money a logger uses to produce a ton of wood from stump to mill or what mill or dealer pays the logger to do the same?

Tommy, Good question. For this discussion, we are referring to logging “costs” as the cost incurred by a mill or landowner for logging services. From the loggers’ perspective, this is the logging rate against which they compare their out of pocket costs of production.