My older daughter* likes to tell the following joke:

“Why did the banker quit his job?”

“Because he lost interest.”

This came to mind while reading a recent New York Times article on the power of yield curves as recession prognosticators (“What’s the Yield Curve?” by Matt Phillips, NYT, 6/25/18). For me, the key point in the article reinforced the practical implications from interest rates ‘getting out of line’ on the yield curve. Decisions critical to economic growth and integrity, including capital investments and pension obligations and debt financing, reference the yield curve as a guide and justifier.

When the yield curve flattens or, ominously, inverts, we lose interest. This has implications for investment returns and the values of assets ranging from stocks to bonds to timberlands.

Before exploring these implications, let’s revisit a previous post on how we apply yield curves.

Yield Curve Refresher

Treasury yields refer to the total amount of money you earn on U.S. Treasury bills, notes or bonds sold by the Treasury Department to pay for the U.S. debt. Remember: Treasury yields fall when demand increases for Treasuries, which investors view as safe investments. As with commercial real estate and timberlands, when prices go up, expected returns on capital invested go down. Treasury yields change daily because few investors hold them to term. Rather, investors resell them on the open market.

We care about Treasury yields because when they increase, so do interest rates on mortgages and business loans. This, among other things, increases the cost of building and buying homes.

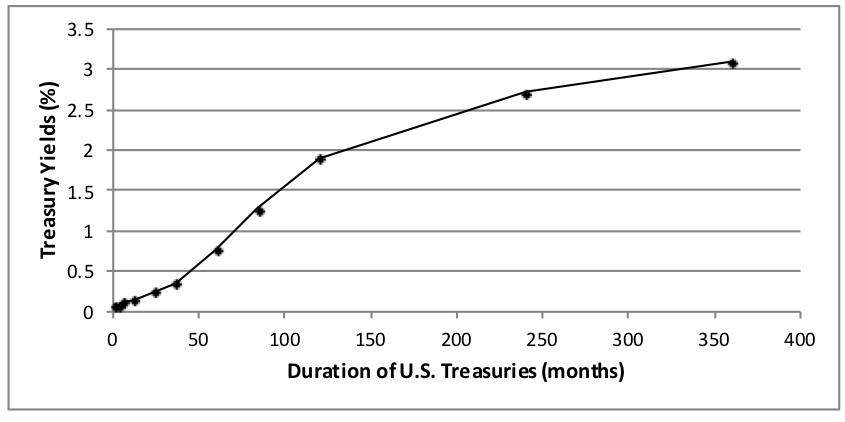

Typically, the government offers higher yields for longer maturities. Why? Because investors require higher rates of return for locking up their capital for longer periods. The figure below provides an example of a yield curve based on U.S. Treasuries as of March 5, 2013.

What do analysts look for? A steep yield curve, for example, where long-term yields far exceed short-term yields, signals the start of an economic expansion. When investors expect economic growth, they also anticipate higher inflation and interest rates, which may lead them to sell their long-term bonds. This drives down the price of bonds and boosts yields.

Alternately, an “inverted yield curve”, where short-term yields temporarily exceed longer-term yields of bonds with the same credit quality, can signal an economic recession. Inverted Treasury yields occurred in April 2000, prior to the 2001 recession, and in January 2006, prior to the 2007 recession. Currently, rates have been rising and the yield curve continues to flatten, raising concerns about inversions and recessions.

Investment Return Implications

In our world, U.S. Treasuries remain a common benchmark for timberland investments. Why? Relative safety and low risk over long time frames. Institutional investors look at Treasuries and think, “well, we need to generate AT LEAST those numbers for taking on timberland assets.” However, U.S. Treasuries, thanks to a robust secondary market, are more liquid than private timberlands, making them convenient benchmarks for publicly traded timber REITs, as well.

For reference as of Friday June 22:

- Timber REITs (CTT, PCH, RYN and WY) generated dividend yields ranging from 2.82% to 4.46%.

- Private timberlands returned 3.63% in 2017.

- U.S. 10 and 30-year Treasuries yielded 2.90% and 3.04% respectively.

The theme of timberland investment returns and macroeconomic indicators will be part of the December 13th “Wood Flows & Cash Flows” event in Atlanta.

*She’s 11. Blame me for her sense of humor.

Leave a Reply