World events and shifting in capital markets increase our awareness and interest in the broader range of disruptions potentially relevant to forestry. How should we think about these?

The first post in this series summarized the current economic situation in the U.S. and implications on timberland investment valuations. This second post introduces a simple approach to help evaluate the magnitudes of impacts on forestry or mill investments from potential changes, good or bad.

Framing Disruptions

When thinking through the mechanisms by which disruptions affect forestry-related cash flows, I often ask two simple questions rooted in economic fundamentals:

- Big or small? In other words, how impactful, whether positive or negative, would we expect this disruption or change to be on forest supplies or wood demand?

- Long or short? What is the likely duration, whether positive or negative, of this disruption or change on supplies or demand (in the market or industry)?

This high-level framework is directional. It focuses on the relative importance of potential disruptions. It also addresses the analytic vagaries of qualitative analysis. A big impact for a single forest owner can be small for the overall market. Think in terms of “tactics” versus “strategies.” Disruptions that get handled on the ground via operations tend to qualify as shorter or smaller in this framework, while anything that requires a Board meeting or an act of Congress better reflects longer-term disruptions affecting future capital allocation and strategic advantage.

Consider the impacts of natural disasters on timber markets. In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina, a Category 5 event, struck the Gulf States, brutally affecting homes, forests and infrastructure. As a disruption, how would we provide context to its impact on timberland owners? Consider our two questions to organize our thinking:

- Big or small? Big event locally; devastating to some forests and damaging to many.

- Long or short? Short-term increase in supplies; negative impact on value.

Figure 3 summarizes this assessment spatially. In sum, a single Category 5 disruption degrades current values through temporarily flooding the local market with damaged timber. While we have little control over the event, options exist to salvage value. And research indicates the impact on stumpage values works its way through the system in 12 to 24 months. The event is short-term because it did not change the long-term fundamentals of wood demand or forest ownership.

Figure 3. Mapping Disruptions: Example of Hurricane Katrina

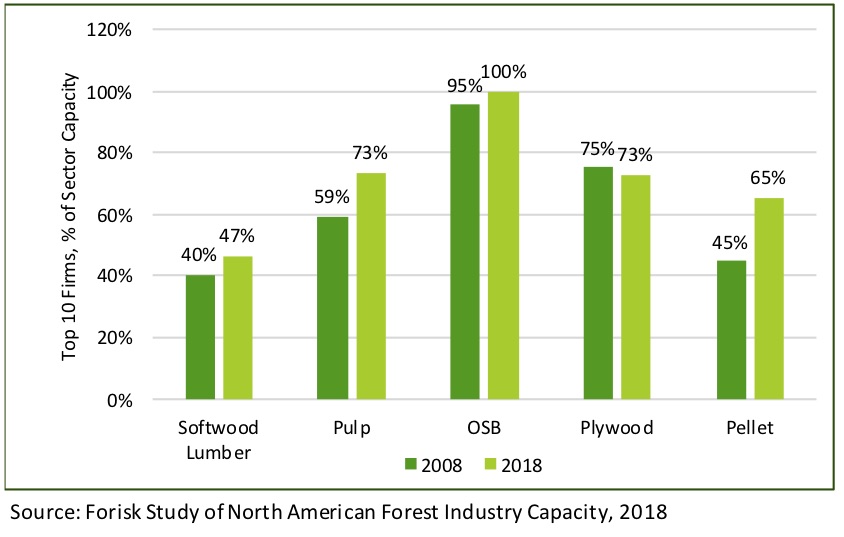

Many events disrupt locally, but not the industry and vice versa. An example is consolidation, which varies across industry sectors and geographic regions. Strategically, the issue has grown in importance as consolidation increased in most forest industry sectors over the past ten years based on Forisk industry analysis (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Top Ten Firm Capacity by Sector in North America

To address inherent dilemmas and disagreements in strategic planning, we prioritize the tracking, aggregation and analysis of confirmable physical facts. This helps test ideas and decisions by, for example, confirming the locations and needs of wood-using mills. The capital-intensive nature of forest industry expansions depends on a solid evaluation and understanding of the current situation paired with a defensible outlook on potential disruptions.

When investing in U.S. timberland or wood-using capacity, we either invest in established forests with mature wood markets, or we invest in areas that require development of the forests and/or wood markets. Using the approach outlined above, how do we develop strategies and assess exposures across multiple disruptions for these situations locally?

We address this in Part III.

Leave a Reply